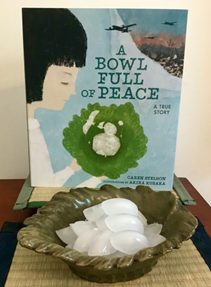

For two hours on a Saturday morning, I sat at a kitchen table with a potter whose initials are K.M. Together, we stared at Sachiko’s grandmother’s bowl. The real bowl. The one that belonged to Sachiko’s grandmother. The one that had survived the Nagasaki atomic bomb. The same one Sachiko had given me as a gift for bringing her Grandmother’s bowl back to life in the picture book, A Bowl Full of Peace. Available May 2020, the picture book is a re-telling of Sachiko’s survival of the Nagasaki atomic bomb and her pathway to peace for young readers. I was overwhelmed when Sachiko gave me her Grandmother’s bowl. I had the same emotional feeling as I sat with K.M. We studied the bowl together as if it were the last object on earth.

I was at K.M.’s kitchen table that Saturday because I had asked him if he could create a replica of Grandmother’s bowl. I wanted to bring a replica to classrooms during author visits. Kids could hold the bowl. Feel the weight of it. Pass it to the next child in the circle. Understand the importance of the bowl and its message. K.M. had agreed to my request.

Japan has one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world, beginning in Neolithic times. Japanese potters have fired earthenware, stoneware, glazed pottery and porcelain in kilns through the ages, turning the craft into an art recognized world-wide. Pottery continues to be an art held in high esteem in Japanese culture, and in the Nagasaki area, pottery villages are alive and well. K.M. knew all of this even before I sat down at his kitchen table.

“This bowl was probably made by a family of potters near Nagasaki, most likely in an assembly-line fashion.” K.M. ran his fingertips over the bowl’s surface. “One family member may have made the base. Another shaped the leaf. Another trimmed the wavy edges of the bowl. One member likely glazed it. Another slipped it into the kiln.” I nodded, imagining the ceramic process. K.M. continued. “Perhaps this leaf motif is the spring or fall model the Nagasaki family would sell in the marketplace.” Deep in thought, K.M. turned the bowl this way and that.

K.M held the bowl to the light. “See this,” he pointed at a slight indentation. “That may be the thumb print of the original potter before he slid it into the kiln.” I squinted and thought I could make out the imprint.

“I wouldn’t suggest this.” K.M. glanced at me. “But if you took a little chip from the bowl and did a mineral analysis, you could trace the exact clay pit near Nagasaki the potter’s family used to make their wares.”

I looked at Grandmother’s bowl in wonder. The entire bowl was transforming into a metaphoric fingerprint. A thought passed through my mind. If I traveled back to Nagasaki, would it be possible to find the family who made Grandmother’s bowl?

K.M. turned the bowl over and peered at its bottom. “No signature, no stamp.” he pointed. He placed the bowl on the table and paused. “I’ll make a replica bowl for you, but I don’t want to take any credit for it. If the original artist made the bowl anonymously, I will be anonymous, too.”

Here lies the reason I call my new potter friend, K.M.

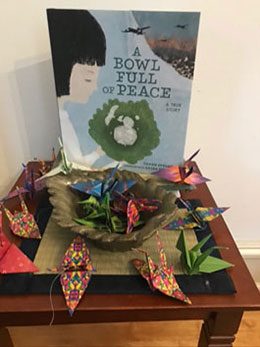

A few months later, I received an email from K.M, “The bowls are done.” When I arrived at his home, four likenesses of Grandmother’s bowl sat brightly on his kitchen table. The bowls were shaped as leaves, just like Grandmother’s bowl, and sparkled with green glaze.

“They’re beautiful,“ I said with genuine gratitude—but the new bowls were not replicas.

“I couldn’t do it,” K.M. said. “The first bowl I made looked just like Grandmother’s bowl, but I wasn’t happy, and I couldn’t understand why. I ended up throwing the bowl away. These bowls are purposely a likeness—not a replica.”

I bowed. “Domo arigato gozaimashita. Thank you. I understand.”

An artist doesn’t copy someone else’s art and still call him or herself an artist.

The real Grandmother’s bowl, the one Sachiko Yasui gave me as a gift, is safe in my office cupboard. The four likenesses of the bowl are in my closet, waiting. I can imagine sitting on a classroom rug, reading a Bowl Full of Peace to children, a new Grandmother’s bowl in the middle of the circle. Sachiko filled the bowl with ice every August 9 to commemorate the atomic bombing of her city at the end of World War II. As she watched the ice melt, she prayed for world peace.

After reading, A Bowl Full of Peace, I’ll ask the children, “Instead of ice, what part of peace can each of us put in the bowl?

1 thought on “A Bowl Full of Peace”

Thank you. So very very sorry that Sachiko has passed away, but her family’s bowl (and, her family) live on to other lives in our hearts through her story. As long as children and people continue to say her name, she is as real as if standing before us.

Peace in our time!